Sanjay Gandhi vs SBI Chairman R.K. Talwar: The Untold Story of the 1970s

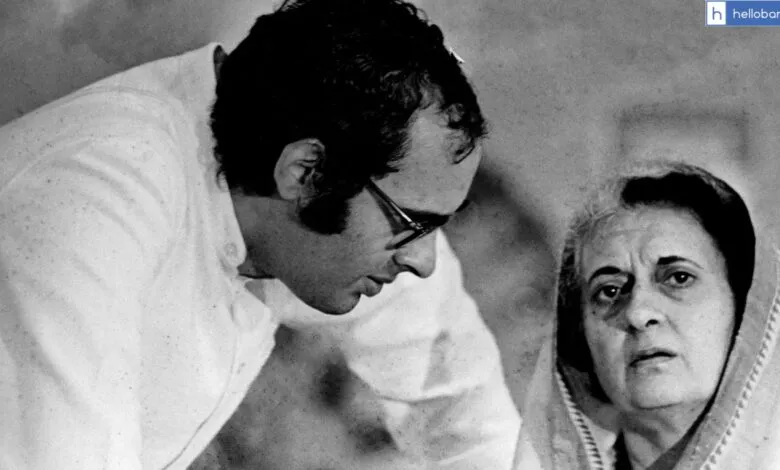

In the 1970s, when Indira Gandhi’s government was at its peak, Sanjay Gandhi had become extremely powerful. Many people saw him as the real centre of authority. Today, in this article, we will read about an untold story from that period – the story of Sanjay Gandhi and the then Chairman of SBI, R.K. Talwar.

The dispute began with a cement company. The company was unable to repay its loan because of poor management. SBI was ready to restructure the loan, but the bank added one condition — the company must remove its current promoter-chairman and bring in a professional manager. Without this change, SBI refused to offer any relief.

The company’s promoter was close to Sanjay Gandhi, so he took the matter to him. Sanjay Gandhi ordered SBI to remove the condition and give concessions to the company. But SBI Chairman R.K. Talwar (1969–1976) refused to follow this order. The Finance Minister then called him to Delhi, but even after the meeting, the issue remained unresolved.

Sanjay Gandhi then asked the CBI to investigate Talwar. But the agency also found nothing against him. After this, the government amended the law related to SBI, and Talwar was forced to go on leave. This amendment later became known as the “Talwar Act.”

N. Vaghul, who began his career at SBI, mentioned this incident in his book. He wrote that Talwar was known as one of the most honest, fearless, and visionary chairmen in Indian banking. Yet, Sanjay Gandhi’s anger created huge pressure on India’s largest bank.

Vaghul explained that the cement company kept making losses, so SBI reviewed the loan. The bank found that the main problem was weak management. SBI offered a restructuring plan but said the promoter, who was also the chairman and CEO, must be replaced. This condition started the whole conflict.

The promoter, being a friend of Sanjay Gandhi, asked him to get this condition removed. Sanjay Gandhi called the then Finance Minister, C. Subramaniam, and instructed him to direct SBI to withdraw the condition. The minister then called Talwar. Talwar reviewed the case file and said that the bank’s condition was correct and could not be removed.

The next day, the Finance Minister again summoned Talwar and said that the order had come from the highest authority — meaning Sanjay Gandhi. Still, Talwar did not agree.

When Sanjay Gandhi heard that the SBI Chairman would not obey his order, he called Talwar for a meeting. Talwar refused and said that Sanjay Gandhi did not hold any constitutional post, so he had no reason to meet him. This angered Sanjay Gandhi, and he then ordered that Talwar be removed.

At that time, removing the SBI Chairman was not easy. The SBI Act clearly stated that the Chairman could not be removed without a valid reason. So the government tried another method. The Finance Minister offered Talwar a new post — Chairman of the Banking Commission. Talwar replied that he could handle both roles without leaving SBI. Hearing this, the minister became upset.

Vaghul writes that Talwar then said, “It seems you are very insistent that I should not remain the SBI Chairman.” The minister finally admitted that the issue was about the cement company and warned Talwar that if he did not resign, he would be dismissed. Talwar firmly said he would not resign.

The government again used the CBI to find a case against Talwar. The CBI discovered that Talwar had forwarded appeal letters to industrialists for donations to the Auroville project. But these were simply copies of a letter signed by UN Secretary-General U Thant and the Prime Minister. No industrialist said that Talwar had pressured them. So the CBI had to close the case.

Frustrated, Sanjay Gandhi ordered an amendment to the SBI Act so that Talwar could be removed without giving any reason. At that time, the opposition was in jail, and Parliament easily passed the change.

After the amendment, the Finance Minister gave Talwar his final warning: resign or face dismissal. Even then, Talwar did not give up. The government still did not dare to fire him directly. Instead, he was sent on 13 months’ leave, and the Managing Director took charge of the bank.

Vaghul writes that on the evening R.K. Talwar left the bank, almost no one came to see him off. People were scared. Even showing support for Talwar could be seen as a crime.